Perseverance rover captures a surprise dust devil while taking high-resolution selfie on Mars

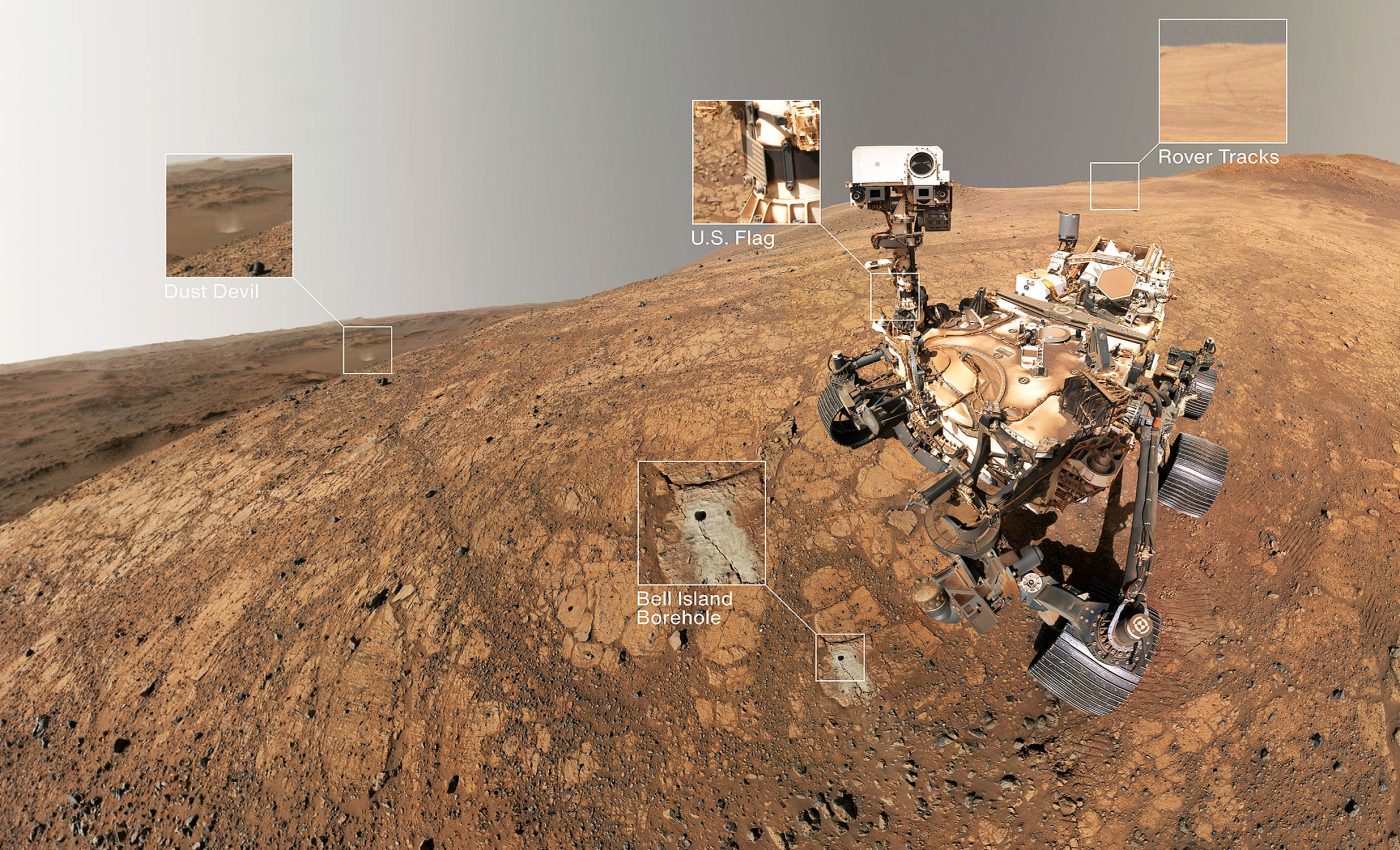

When NASA’s Perseverance rover paused on May 10 to take a celebratory self-portrait, the robot got more than it bargained for. In the distance, a twisting plume of red dust – what scientists call a dust devil – spiraled across the landscape near the rover.

The dust devil photobombed the shot, turning an engineering record into a textbook example of Martian weather at work.

The image commemorates sol 1,500 of the mission. A sol is a Martian day, lasting 24 hours and 39 minutes. On Earth’s calendar, 1,500 sols is roughly four years and two months since Perseverance landed in February 2021.

During that time the rover has trundled more than twenty-two miles, drilled thirty-seven rock targets, collected twenty-six core samples, and sent home some of the most detailed planetary science ever captured on another world.

Dust devils and Mars rovers

The latest portraits were taken while the rover sat on a high part of Jezero Crater’s western rim, called Witch Hazel Hill. This vantage point has been under study by the science team for several months.

Justin Maki, the imaging lead at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California, is quick to point out why the resulting panorama excites engineers and scientists alike.

“The rover self-portrait at the Witch Hazel Hill area gives us a great view of the terrain and the rover hardware,” Maki explained.

“The well-illuminated scene and relatively clear atmosphere allowed us to capture a dust devil located three miles to the north in Neretva Vallis.”

That narrow channel once fed water into Jezero, delivering sediments that now help researchers read Mars’s ancient climate.

On this particular sol, it also delivered a swirling column of airborne grit – evidence that the planet’s thin carbon-dioxide atmosphere still carries surprising energy.

Rover selfies and health checks

From an operational standpoint, each selfie doubles as a health check. Photographs help mission teams track dust on solar panels, check for damage, and confirm cables and joints remain intact.

“After 1,500 sols, we may be a bit dusty, but our beauty is more than skin deep,” said Art Thompson, the rover’s project manager at JPL.

“Our multi-mission radioisotope thermoelectric generator is giving us all the power we need. All our systems and subsystems are in the green and clicking along, and our amazing instruments continue to provide data that will feed scientific discoveries for years to come.”

The art of Martian selfies

Capturing a high-resolution portrait on Mars is far from a point-and-shoot endeavor. The main camera responsible for these mosaics is WATSON, short for Wide Angle Topographic Sensor for Operations and eNgineering, mounted on the end of Perseverance’s seven-foot robotic arm.

Because WATSON cannot see the mast – the rover’s “head” – unless the arm swings out and the mast swivels to face the camera, the imaging sequence demands extreme choreography.

Megan Wu, an imaging scientist with Malin Space Science Systems, oversaw the latest routine. “To get that selfie look, each WATSON image has to have its own unique field of view,” she explained.

That translates to sixty-two painstaking arm movements and sixty-two overlapping frames, which were later stitched together on Earth.

The team had the rover turn its mast toward Bell Island and captured three more frames. They merged those too, so the final product shows Perseverance gazing both into the lens and down at its newest borehole.

Perseverance’s big moments

The bright lighting in the photo is no accident. Mission planners time these sessions when the Sun’s angle will illuminate both the rover’s deck and the terrain behind it.

The resulting shadows fall cleanly beneath the chassis, offering depth cues that help viewers appreciate just how rugged Witch Hazel Hill is.

Jezero’s rim rises in the far background, a reminder of the crater’s violent birth by impact billions of years ago.

Though undeniably photogenic, the dust devil is more than a backdrop. Such vortices arise when solar heating warms the surface, causing pockets of air to rise and spin.

On Earth, they are common in deserts; on Mars, where the atmosphere is only about one percent as dense, they can stretch hundreds of meters tall yet remain almost transparent until they pick up reddish dust.

Scientists value these whirlwinds for cleaning panels, revealing wind patterns, and explaining how dust rises high into the atmosphere. The plume in Perseverance’s selfie drifted through Neretva Vallis, three miles away, hinting at breezy conditions in Jezero.

Perseverance rover’s legacy

Perseverance’s immediate science goal remains the search for signs of ancient life. The twenty-six cores sealed so far are destined, NASA hopes, for eventual return to Earth by a future mission.

On Earth, scientists will analyze the samples for molecular fossils, isotopic clues, and mineral histories Mars tools can’t detect.

Each sample represents a chapter in Jezero’s watery past. Together, they might reveal whether microbes ever thrived on the Red Planet.

In the meantime, the rover continues its trek. Its next destination, a spot nicknamed “Krokodillen,” promises layered rocks that may record shifting environmental conditions.

As Perseverance rolls onward, the planet’s relentless dust will keep settling on its chassis, but every grain adds context to the story the rover is helping to tell: a story of wind, water, and time on a distant world.

Thus, the 1,500-sol selfie is more than a milestone memento. It is a technical achievement, a weather report, a clean bill of health, and a literary illustration of perseverance itself.

“Having the dust devil in the background makes it a classic,” Wu concluded.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–